Behind the Design: A Celebration of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Art and Cultures

- Jun 20, 2023

- History

- 10 minute read

The 2023 National Indigenous Peoples Day commemorative $2 coin is an invitation to learn about and honour First Nations, Inuit and Métis histories and heritages. Taking a cooperative approach, three artists—Megan Currie, English River First Nation, Myrna Pokiak (Agnaviak), Inuvialuit Settlement Region and Jennine Krauchi, Red River Métis—actively developed the coin design together.

The 2023 National Indigenous Peoples Day commemorative $2 coin is an invitation to learn about and honour First Nations, Inuit and Métis histories and heritages. Taking a cooperative approach, three artists—Megan Currie, English River First Nation, Myrna Pokiak (Agnaviak), Inuvialuit Settlement Region and Jennine Krauchi, Red River Métis—actively developed the coin design together.

It was the first time in the Mint’s history that three artists jointly developed a design for a Canadian circulation coin. Each representing unique backgrounds and cultures, the artists brought their own perspectives and experiences to create beautiful and harmonious art. The rich expressions of cultures, traditions, and heritages that make up the design are drawn from a variety of inspirational sources, each unique to the artist.

Below, the three artists share their personal insights on their designs, and what the design elements they chose represent.

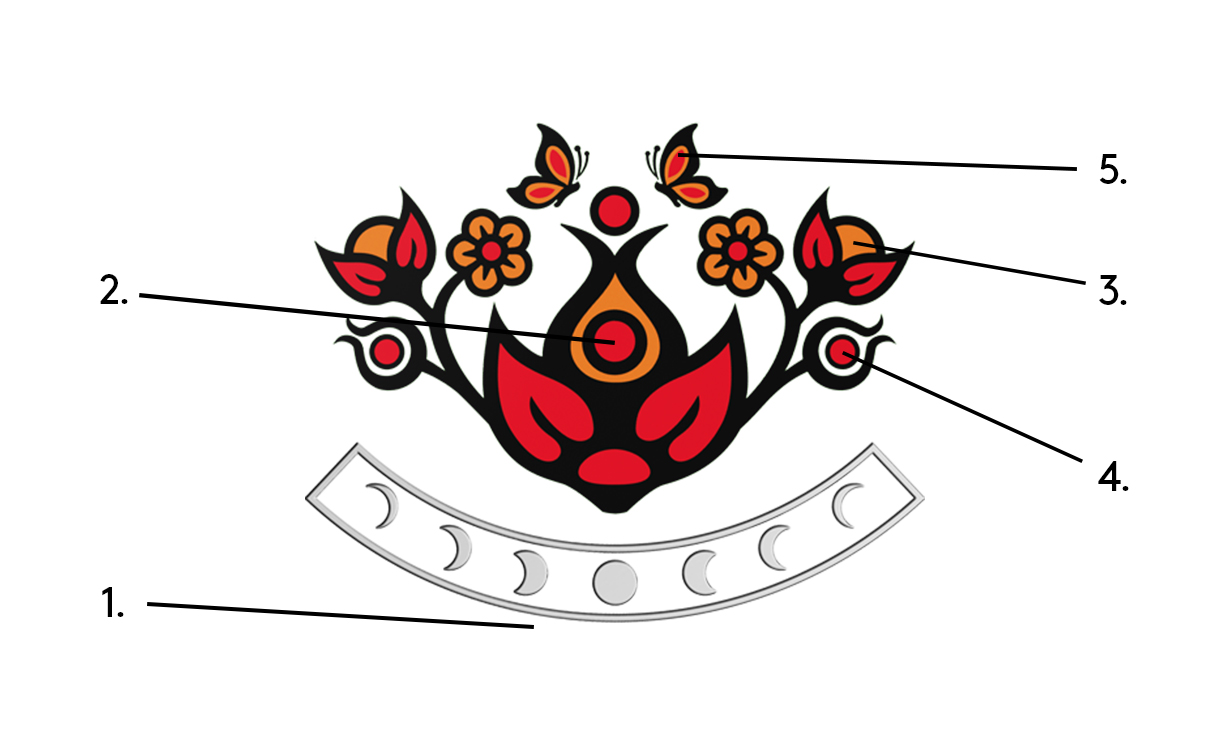

First Nations

1. Grandmother Moon

The top sections of the design honours Grandmother Moon. There are seven phases of Grandmother, representing our past, present and future and the seventh Generations teaching. This teaching reminds us of our commitment to the seven generations coming after us in our words, work and actions, and to continue to honour and remember the seven generation who came before us.

2. Blossoming flower

Central within the main design is a blossoming flower containing an adult figure raising a child above them. This reminds us to honour our children and to acknowledge that there is hope for our future.

3. Forget me not

The forget-me-not flowers honour our past generations, our survivors, and those who have moved on to the spirit world. The five petals hold space that we should never forget; the genocide of our people, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, those who attended Residential Day and Boarding Schools, ‘60s scoop survivors and our veterans. The flowers on the outside of the design contains a rising Grandfather Sun, signifying a new day and the opportunity for all Canadians to move forward and commit to reconciliation.

4. Circles and berries

The four circles within the main flower and the berries acknowledge; the four stages of life, the four sacred directions and the four seasons. The berries, often utilized in our sacred ceremonies, remind us to continue to honour and thank Mother Earth for her gifts of medicine and food.

5. Butterflies

The butterflies are a symbol of transformation, metamorphosis, and balance. The design as a whole is balanced, and a reminder that we need to live a balanced life with our spiritual, mental, physical and emotional health.

About the Artist: Megan Currie

Megan Currie is a proud Dene woman from English River First Nation. One of her first connections to her culture was through artwork, and she was greatly inspired by the Native Group of 7. Over the years, she has fostered her belief in visual sovereignty, which guides all her work. The founder and creative director of X-ing Design, a 100% Indigenous owned and operated graphic design and studio, Megan has developed a reputation as an Indigenous design trail blazer. Her unique focus in Indigenous design and visual sovereignty is showcased in her diverse portfolio of work. Megan’s global education, combined with her First Nation's background, provides her with a unique perspective on design that is evident in her techniques, styles and design process.

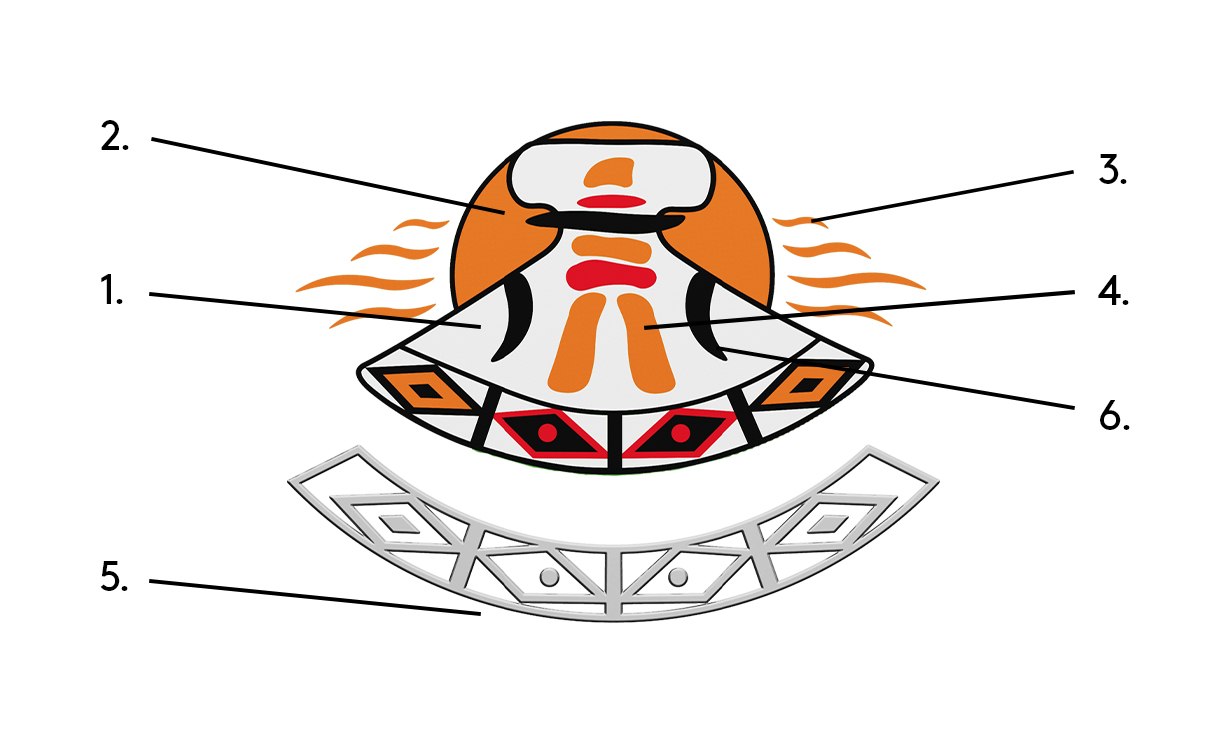

Inuit

1. Ulu

Ulu, a tool once made from slate, often found in art while its function continues to be for sewing and preparing food to feed our families. An Ulu is symbolic of Inuit throughout the world and from east to west Inuit can identify where the Ulu originated because of its shape. The Ulu in my design is symbolic of the Inuvialuit of the Western Canadian Arctic and the community of Tuktoyaktuk.

2. Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun, from time immemorial the midnight sun has offered its light for Inuit from the Arctic circle to the Northernmost regions of Canada. As it moves across the skyline the sun goes through a series of yellows, oranges, and reds, offering colours that are used in art and storytelling.

3. Ocean Waves

Ocean waves, a timeless event that Inuit watch in anticipating of hunting and traveling. Inuit have lived for millennia alongside the coast of the Arctic Ocean, connecting families and friends from Alaska to Canada to Greenland to Siberia. Harvesting and traveling along the coast and over the rolling waves has bridged our communities together. The vast Arctic Ocean has provided the nutrients from the mammals and fish generation after generation. As a child, my family has traveled along the coast by boat, dog team, snowmachine, and airplane from one hunting camp to another. I am an ocean girl at heart as so many other Inuit boys and girls can relate to.

4. Inukshuk

Inukshuk, a symbol of people, directions, connections, successful harvests, and our ancestors who shared the same scenery as we are gifted today. Inukshuk is also a symbol that Inuit in the East are known to use much more than in the West as rock is in abundance in the Eastern Arctic and Arctic Islands. I chose this symbol as I spent a month hiking at Tuktut Nogait National Park, outside of Paulatuk, a small community within the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. I hiked for thirty days along the Little and Big Hornaday Rivers with three others documenting our history through the Archaeological artefacts that remain. The Inukshuk tells many stories of our ancestors. One beautiful memory is walking on top of high hills above the river and a line of Inuksuit stood from where I stood to as far as I could see. The Inuksuit were to resemble man and used to drive migrating caribou herds to a chosen hunting location towards hunters, who at the time used traditional tools, made with slate, wood, and bone. Since that experience, I have always felt a deep connection to Inuksuit as they are a symbol of Inuit from past to present and remnants of our ancestors that stand tall and strong, a reminder to myself never to give up.

5. Delta Braid

Delta Braid, a design that has been adapted from the traditional Inuit adornment on clothes with fur, hide, and materials, coloured from berries, plant roots, and most notably, red ochre rock to stand out with colour. Geometric patterns are identifiable features on Inuit clothing to tell a story of a family, community, and region. The patterns are often used in Inuit art and clothing, adapting to modern fabrics, beads, and threads that produce designs that connect us to our ancestors. I made my first traditional dancing parka and the inspiration for the trim came from my family of Inuit from the Western Arctic of Canada all the way to Alaska. I was gifted a muskrat parka from our Alaskan relatives, where the geometric patterns are a highlight of the parka. I have also been gifted a parka trimmed with Delta Braid made by my auntie Annie. This artform is signatory to families living in the Mackenzie River Delta area. The trim requires patience, colour, geometric patterns and is an artform that resembles people of the Delta, and most recently including our neighbors from the Gwich’in Nation with ties to the Delta.

6. Tusks

Tusks, a signatory design on Inuvialuit clothing with ties to Inupiat in Alaska. This illustrates the borderless connections Inuit across the circumpolar region have with one another and it connects me to my family’s history. I did my first degree at the University of Alaska and once I graduated, my uncle Boogie and father gifted me a trip to Barrow and Kaktovik, Alaska, to meet our relatives. This was the first time I truly made that connection to the clothing I grew up wearing and realized how similar we are to so many other Inuit in the world. Tusks continue to be used on parkas and other artforms including carvings, clothing, and accessories.

About the Artist: Myrna Pokiak (Agnaviak)

Myrna Pokiak (Agnaviak) is an Inuvialuk from Tuktoyaktuk in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. She currently lives in Yellowknife with her family.

“I love art, but mostly, I love my Inuvialuit culture and giving my best effort knowing what my ancestors sacrificed for the opportunities I am gifted with today. I believe as an artist, from a generation where I learned primarily from the land and sea, raised in a log house with sod walls and floors, my connection to culture is immeasurable as I have lived through a generation of change with two world views. My art is a depiction of my lived experience and has meaningful and emotional connections for each design I have chosen to represent what it means to me to be Inuvialuit.”

Métis

1. An infinite symbol that is stylized to look like two fiddles

A well-known national symbol of the Métis Nation is their historic and national flag. Referred to frequently as the ‘infinity flag’ it has a white infinity symbol and reflects the Métis nation as a distinctive people who will survive and be united forever. Métis peoples fly either an infinity symbol with a blue or a red background.

The Métis people are a spirited people, who have always had a love of music and dance. They are renowned worldwide for their unique fiddle music that compliments their distinctive high energy dance known as ‘the jig’ or ‘the Red River Jig’. The main musical instrument of the Métis is the fiddle.

2. The Métis sash

The sash is recognized as a part of Métis culture. Historically, it was part of the clothing worn by Métis people (predominantly men) every day for both fashion and function. It had many uses such as a holder, washcloth, bridle or saddle blanket. In contemporary times, the sash is worn by Métis people today (men, women, and non-binary) in celebration of their culture and identity. It can be worn on one’s waist just above the hip or across one’s shoulder.

3. A portion of a red river cart wheel

As one of the best-known symbols of the Métis culture, the versatile Red River cart directly, contributed to the commercialization of the buffalo hunt and fur trading industry. The cart was constructed from wood, bound together with rawhide, and features broad, large, dished wheels. It was these wheels which were well-adapted to prairie conditions, easily going through muddy or marshy terrains. The cart's box was mounted over the axel and could be filled with large volumes of meat, furs, and other goods vital to the buffalo hunt or fur trade. To add to the cart's versatility, the wheels could be removed, allowing it to be put into water and act as a barge, or, with leather strapped to the bottom, a boat. In addition, with minimal alterations, the cart could be turned into a sleigh during the winter months.

4. A beaded five petalled flower

The five-petal flower has long been adopted by the Métis who are known as the “Flower Beadwork People”. Métis women learned embroidery from the Gray Nuns. When beads arrived they soon incorporated this work into their own style of art form. This flower is indicative of prairie roses but also of other prairie flowers.

5. Spirit bead

Often; in Métis beadwork, one can see berries, leaves and Mouse-tracks – little ticks along the stems of flowers etc..., representing the tracks of a mouse in the snow and Spirit Bead representing humility and the notion that nothing can ever truly be perfect. Beadwork was made for family and horses and dogs and spoke directly to the pride and love of the Métis for their culture.

About the Artist: Jennine Krauchi

Jennine Krauchi is a Métis beadwork artist and clothing designer. She has spent many years learning from her elders; both Métis and First Nations. Jennine has made numerous garments for notable dignitaries, and has created replicas and artworks for several museums in Canada and Europe. She has also been commissioned to do replicas for Parks Canada and the Manitoba Museum. Jennine has taught Métis beadwork across Canada and Europe, and has received the Order of the Sash from the Métis National Council and most recently, the Indspire Award for Culture, Heritage & Spirituality for her years of contributions to the enrichment of Métis culture.

The most important message that Jennine would like to impart is “To keep our cultures alive, whether Métis, First Nations, or Inuit and to pass this knowledge on to our future generations.”

Bring the celebration to your collection: learn more about National Indigenous Peoples Day and the 2023 commemorative circulation coin minted in its honour.

Thank you to the incredible artists who have shared their art through these coins, and to the numerous individuals and organizations who shared their time with us to help bring such an important and meaningful coin to life.